Amtrak’s Mardi Gras ServiceSM offers a chance to visit some fascinating Gulf Coast cities – London-based travel journalist, Jacqui Agate, gets on board.

"C’mon take me to the Mardi Gras, where the people sing and play …” A cheerful rendition of the 1970s Paul Simon song drifts down the train carriage, sung by a chorus of bead-clad passengers. Across the aisle a woman’s sequined top glitters purple, green and gold. It isn’t carnival season in New Orleans — it’s summer — yet the sense of celebration is palpable.

There’s much to celebrate about this journey. Amtrak’s restored Mardi Gras service between New Orleans in Louisiana and Mobile in Alabama will now curl 145 miles along the US Gulf coast twice daily, stopping in the Mississippi cities of Bay St Louis, Gulfport, Biloxi and Pascagoula. And single tickets start from as little as £11 (amtrak.com).

The return of the Mardi Gras service was hotly anticipated

The last train before the relaunch ran in August 2005, then category-five Hurricane Katrina made landfall in the region, claiming at least 1,800 lives and tearing up the rail infrastructure that linked these cities. While freight services resumed within six months, the passenger service was halted. Now, as communities mark the 20th anniversary of the disaster, the train is finally on the move again.

Jacqui's Insider tip: Time your table at Dauphin’s Restaurant for sunset — its 34th-floor perch grants you dazzling views of Mobile Bay

The train initially runs parallel to Interstate 10, with cars on the highway outpacing us. You could drive from New Orleans to Mobile in about two hours; the train takes almost double that. But speed isn’t the point. The re-established route is as symbolic as it is practical, a marker of Gulf-coast resilience and a reminder that these cities are linked not just by rails, but by shared history and spirit.

On board there’s a café car, reclining seats and great views.

“This new service will connect us with our nearest neighbours,” says Tyler Black Hernandez, from New Orleans. A non-driver, he’s day-tripping to Mobile with his mother. “Mobile, Biloxi and New Orleans were all capitals of French Louisiana once. Now we’ll have a point of connection to these historic communities, which also serve as our beach getaways.”

The train is an experience in itself. There’s a well-stocked café car and business and coach class each have wide, reclining seats with ample legroom that prove to be ideal vantage points as the Gulf coast views whip by. Eventually, city vistas unravel into a tangle of coastal marshes; a snowy egret skims the rushes and a lone fishing boat ploughs the waters.

Mobile is my final stop and I make early acquaintance with the city’s French heritage. Stately portraits of King Louis XIV and the Mobile founder Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville hang in gilded frames in the newly renovated Admiral Hotel, my base for a few nights.

Outside there are echoes of New Orleans — wrought-iron balconies line Dauphin Street, accordion music wafts from a souvenir store strung with Mardi Gras beads and oaks shade Cathedral Square, home to the oldest parish on the Gulf coast, established in 1703.

“New Orleans is our younger, noisier brother. That’s how we can be the birthplace of Mardi Gras — New Orleans was still a swamp when we were first celebrating…” says Bella Myers, who leads our Bienville Bites food tour that evening. “But there’s a synergy between the cities and a shared history.”

Indeed, Mobile was founded 15 years before New Orleans, and Myers begins this deep-dive into city history at the upscale Dauphin’s restaurant. On the menu is Joe Cain dip, a spinach-and-artichoke mix with Conecuh sausage named for the Confederate veteran credited with reviving the Mardi Gras in Mobile after the Civil War (mains from £20; godauphins.com). Joe Cain Day remains a Mobile tradition, marked with a family-friendly parade on the Sunday before Fat Tuesday. “Mobile was the city that Mardi Gras built,” Myers says.

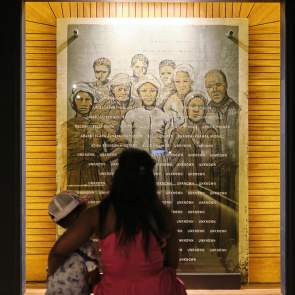

Further stops include Post (cocktails from £7; outsiderspresents.com), a swish bar whose owner, Matt LeMond, hails from New Orleans (“That’s what we do,” says Myers. “We move back and forth”); and Wintzell’s Oyster House, a Mobile institution dating from 1938 (mains from £14; wintzellsoysterhouse.com). Along the way Myers shares historical tales, including the story of the “Pelican Girls”, 23 young women sent from France aboard Le Pélican in 1704 to marry settlers and seed the colony. “The Pelican Girls are the mothers of Mobile,” she says.

There’s time for a last dose of history before the train spirits me back to New Orleans. I tour the USS Alabama, a Second World War battleship docked in Mobile Bay (£14; ussalabama.com), and explore Africatown Heritage House, telling the story of Clotilda — the last-known slave ship to bring Africans to the US — and its survivors (£11; clotilda.com).

The Mardi Gras service does more than ferry passengers — it binds a string of Gulf-coast cities with a shared history, heritage and dazzling shoreline. It is a journey well worth taking.

Read the article in its entirety at TheTimes.com. The Times, founded in 1785 as the Daily Universal Register, is the oldest national daily newspaper in the UK and holds an important place as the “paper of record” on public life, from politics and world affairs to business and sport.